Less

of a book and more of a hodgepodge of raves and rants from a man who couldn’t

accept life as it is: this sounds a bit too scathing but bears more than an

element of truth in it. Raves and rants abound but they are so unabashedly

honest, so slanderously abusive, so nakedly, sordidly libertine and at times,

so beautifully poetic that one feels like going back to revisit some of the

passages whose gist wasn’t lucid on the first attempt but turned out to be

heavily-imbued with meaning on the second and the third.

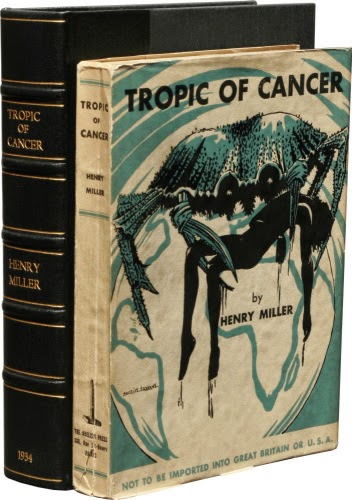

The

cover of the book (my copy) shows a woman in the buff with a prominent derriere,

a smoulderingly-inviting come-hither look but an almost transgender expression

on the half-turned face. It left me a little red-faced at the bookshop’s

counter but I went ahead as boldly as Miller himself would have done when he

chose to have his book out in the public domain, only to be condemned

mercilessly and banned for its shock-value and violently-candid libertinism.

|

| First Edition 1934 |

The

word ‘cunt’ is used innumerable times and the references to women – mostly whores

– wouldn’t be palatable for a reader with a feministic bent of mind: such is

the objectification of the female body. But if it is seen from a pure, honest

libertine’s point of view (taking a cue from Marquis de Sade) – as opposed to

hypocritical prudes – Miller is quite right in suggesting that a whore should

be ‘a whore from the cradle’ rather than a blend of fake feminine refinement

and cold detachment from a sexual act which they perform with ‘eyes staring

vacantly at the ceiling’ while the man is slugging away with his machine.

A whore who is vociferous, who moans and groans with abandon and spews out stuff that a patron wants to hear in such critical, pre-orgasmic moments is one who is admired by Miller for being true to her vocation. Indeed, this might be the crudest example to show it but a vocation demands total submergence of a person in it for it to have any value.

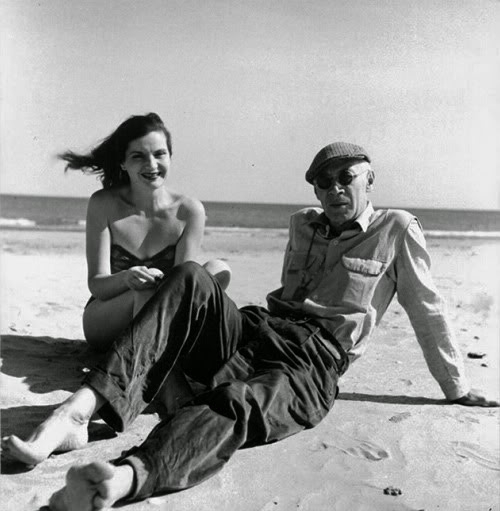

|

| Henry Miller and Twinka |

Occasionally,

Miller delves into reflections and musings on life, existentialism, the human

condition, nihilism, fatalism and many aspects of philosophy which I do not

know the names for. Walt Whitman is held in the highest esteem while Goethe is

vilified with innuendoes. Paris is both censured and praised - sometimes in the

same breath – and the sullied underbelly of the city: the red-light area (inevitably),

the humdrum street-existence, the poverty and hunger which stand heavily at

odds with the opulent image of Paris that most people harbour, is all brought

out with Miller’s nakedly-delivered wisdom.

Occasionally,

Miller delves into reflections and musings on life, existentialism, the human

condition, nihilism, fatalism and many aspects of philosophy which I do not

know the names for. Walt Whitman is held in the highest esteem while Goethe is

vilified with innuendoes. Paris is both censured and praised - sometimes in the

same breath – and the sullied underbelly of the city: the red-light area (inevitably),

the humdrum street-existence, the poverty and hunger which stand heavily at

odds with the opulent image of Paris that most people harbour, is all brought

out with Miller’s nakedly-delivered wisdom.I found Miller’s metaphors and similes too mired in literary fog and often disgusting: ‘polished as a leper’s skull,’ ‘the smile of a fat worm’ and so on; but his writing is not the kind that can be understood and appreciated all at one go. Hence, the knocking and re-knocking at doors that require all your intelligence and patience to reveal what they have in store.

Being

a writer from the early 20th century, Miller too could not fail to

be touched with Gandhi’s ideals but he chooses to refer to it with a revolting

example of a fake Gandhian who is out visiting whores in Paris. The incident of

his making a fool of himself is both humorous as well as stomach-wrenching but

aside from the wry humour, what he says about Gandhi is true. The Indian

edifice indeed stood on a tenuous foundation which was held in place by the

Mahatma but as soon as the great man would exit, the opposing forces of caste,

creed and colour would re-assert themselves and the society would start to

implode. Quite a far-sighted assessment from a man who understood India from a

distance.

Miller is quite opaque at times – umpteen times actually – when his words seem to flow with reckless abandon without a cogent meaning to be derived from them. Many sections of the memoir are the prose-poem kind with a generous use of his extensive vocabulary that draws upon both street-slang and patrician eloquence in equal measure. He calumniates the so-called important people who run the world, the ‘colourless individuals’: the engineers, doctors, lawyers, money-lenders and the like. He attacks the education system which moulds young minds into a set type in order for them to melt into the bog of the teeming banality of the wasteland the world has become. His rebellion is that of a man who wouldn’t want the smallest slice of the commonplace life: he would live the way he wants to, even if it means mooching along the streets of Paris on an empty stomach while still able to get a hard-on, both a cause for celebration and an anatomical riddle to unravel.

Many people would pick up the book for its sexual content as the cover itself suggests or as his entire oeuvre and his reputation indicate. Most characters in the book are sex-starved but even in their worst ramblings, they often spout profound truths for a reader who is patient and incisive. A man who wants loads of books and loads of ‘cunt’ might seem repulsive but it exposes the anguish that lies within many repressed people who are forced to eke out a dreary existence, trapped in a job they abhor. To get a bevy of cunts is their idea of both bliss and release: a libertine’s philosophy all the way but many seemingly innocent and polished people inhabiting the civilized world are great sensualists and even perverts from inside. Miller only reveals the darker side of factotums while cutting down on none of their perversions.